When I asked everyone what I should write about, the biggest answer was “game design”. So here you go.

Before I start, though…you can now get Transparency, one of my favourite Cosmic Dark scenarios, on my Patreon (on the $5 tier). It’s got chases, fights and weird psychological horror. Tell me what you think.

What dice do in roleplaying games

Here’s one thing dice can do in roleplaying games. They can split the story, like this.

For example, you’re exploring a basement and someone hits you from behind. You roll dice to find what happens. If you get an odd number, you’re knocked unconscious. If you get an even number, you’re fine.

Here’s another thing dice can do. They can inject something into the story.

For example, you’re trying to get information out of a barman. You roll dice. If you get an odd number, he tells you what you need to know. If you get an even number, he tells you what you need to know, but then he runs away.

These things are fun! We’re playing the story, we roll dice and we don’t know which way things will go. This, for me, is why we play roleplaying games.1

When we’re designing a game with these two techniques,2 what do we have to think about?

Splitting the story

When you’re using dice to split the story, ask yourself: are both outcomes fun to play?

Here’s the “exploring a basement” example again.

Are both those outcomes fun to play? Not really. If you’re knocked unconscious, that isn’t fun in itself. After all, you can’t do anything. If you’re not knocked unconscious, that seems dull too. It’s hard to get excited about something not happening.

For me, then, this is a bad way of using dice to split a story.3 Here’s an attempt at making it better.

Here, I think “you crash to the floor” is interesting, because it sets up a charged situation with your attacker towering over you. That could go in lots of directions! And “You ride the blow, then wheel around to face them” sets up a fight. Both these lead to interesting situations that I’d want to play.

Injecting things into the story

When you use dice to inject things into the story, ask yourself: are these things reliably fun, even if repeated?

Here’s that example about getting information from a barman again.

This injects “the barman runs” into the story. It’s a staple of detective fiction, because it sets you up for a chase scene.

Here, I think both outcomes are fun to play. If they give you the information, that’s fun. And, if there’s a chase scene, that’s fun too.

But are they reliably fun? Imagine you played a mystery game, in which you interviewed lots of people for information, and they kept running away. You’d play chase scene after chase scene. It’d get dull.4

Here’s an attempt to improve it.

I like this, because “Things get ugly” steers you towards action. But the wording is broad enough to allow for creative interpretation by the players. Perhaps the barman pulls a gun. Perhaps a bullet flies through the window. You wouldn’t get bored with things getting ugly.

Steering towards a narrative

What’s so powerful about these techniques is that they let you steer towards a particular type of story.

Let’s write a game about thieves falling in love. We want to roll dice to decide whether someone picks a pocket. Now, we could do a simple success/fail roll:

But instead, let’s steer the narrative towards a story about thieves in love. First, let’s try splitting the story:

We’ve rolled dice and both outcomes steer subtly towards our “thieves in love” story.

And note how subtle this is! We didn’t write “You fall in love with your victim”: that wouldn’t be interesting if it happened repeatedly. Instead, both outcomes set up intimate situations that might be fun to play through.5

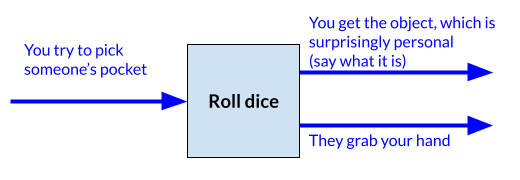

Now let’s steer towards “thieves in love” by injecting something into the story.

Again, we’ve resolved the situation, but we’ve pushed the story in a romantic direction.

All the examples above were simple. Let’s try sometjhing more complex, which we might actually use in a game.

Here’s a rule that splits the story and injects things into the fiction. This time, we’ve introduced an element of choice (i.e. you get to choose between outcomes). The outcomes are fun to play (i.e. they set up interesting situations) and broad enough to play repeatedly. And they steer towards a story about thieves in love.6

The rule is: when you try to pick someone’s pocket, roll a die. If you get an even number, you get something, and choose one: you notice something attractive about them (say what you notice), the object you steal is surprisingly personal (say what it is) or they remember you. If you get an even number, you get nothing, and they choose one: they grab your hand or they remember you.

That’s enough for now.

Tell me what you think! There’s a potential future post about success and failure. We use it as a default in game mechanics, but — as you can work out from the discussion above — I don’t think it always works. We should explore it more.

Of course, there are other things that dice can do: for example, they can make a number (e.g. “hit points”) count down to zero, which adds tension. For the moment, though, I want to focus on how dice can affect the narrative. And there are objects other than dice (coins, playing cards, tarot cards) that can change the story. But let’s focus on dice.

Are there other ways that dice could affect roleplaying games? Could you roll a die to enhance or alter something that’s already happening? For example, if you roll an odd number, this thing seems creepy, but if you roll an odd number, it seems comforting.

But you see this a lot! I think game designers often do this to add peril to rolls: “If you roll low, something bad will happen!”. I get the intention, but you need to make sure the bad thing is actually fun to play, if it does happen.

If this example seems contrived, consider this alternative rule: When you interview someone for information, roll a die. On an even number, they give you the information. On an odd number, they give you the information, but they either run away, pull a gun or reveal themselves to be somebody else. This still suffers the problem that, if these things keep happening, they get dull. You’d get tired of guns, chases and mysterious reveals.

The outcomes are also broad, allowing for creative interpretation. A more specific outcome (“You get a rose”) wouldn’t work. You’d end up with a lot of roses.

It’s interesting to ask: could we actually use this rule in a game, if we wrote other rules like it? Is anything missing? For me, the main thing that’s missing is interaction with other mechanics.

I don't think dice do much beyond being a hard-to-argue-with fidget toy for the socially awkward. Who wants to argue with a little plastic cube? Also, they're seemingly good enough at distancing a player from perhaps a hard to approach subject. I've said as much before. I guess i figured I'd spell it out here, for whatever reason? They're an unassuming buy-in.

I really like this framing. There are some situations were a lot of rolls happen in quick succession (like a traditional rpg combat) and in those lots of binary hit/miss results are ok because it is the aggregate of all of them which tell the story. There are other games, typically more lightweight rules ones, where a single roll can be consequential and that’s where your insights particularly apply.

PbtA games are examples which can suffer from the GM (or the designer!) not making the choices interesting. At their best, it is a lot like your last example, but I still see too many run as “6-? That’s a fail”

It’s certainly thought provoking stuff.